Probiotics - we ARE bacteria - body has 10 times nore bacteria than body cells

Gregor Reid, professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Western Ontario, and director of the Canadian Research and Development Centre for Probiotics.

must hear:

http://podcast.radionz.co.nz/ntn/ntn-20110329-1129-Probiotics-048.mp3

2:45 - The body has 10 times more bacteria than human cells

pass it on...

watch the film: http://www.activia.ca/probiotic/

- Female Health: Can we manipulate the microbes inside us to improve the chance of conception, better ensure a healthy pregnancy and improve human longevity? This emphasis on female health dates back almost 30 years with our studies on using lactobacilli to prevent urinary and vaginal infections. The advent of new technologies and a renewed interest from funding agencies to finally take these issues seriously, has spurred our research.

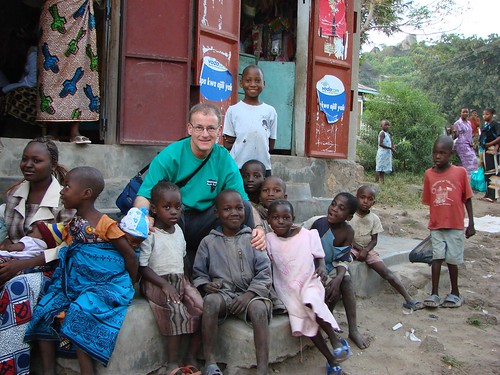

- Affordable Probiotic Foods: Can we create affordable probiotic food to improve well-being and reduce 'toxins' in the general population and people in the developing world? The outstanding work of our Western Heads East students in Eastern Africa setting up probiotic yogurt kitchens, epitomizes our belief that small changes can lead to great things. On a global scale, impacting 350 people in a community with one kitchen, seems infinitesimal, but we view it as one life at a time. We are fortunate to gain access to the amazing Danone Communities project which also aims to bring affordable nutrition to people living at the bottom of the pyramid. Thus, we provide input into projects in Bangladesh, Indonesia and South Africa. Of course, affordability is not a concept exclusive to the developing world, and so we strive to have companies develop healthy foods for people in Canada and other countries who are living on the edge of poverty.

- How do these bacteria work? As the area of probiotics has exploded in recent times, so too has the need to understand scientifically how these organisms function, and also to prove in appropriately designed clinical trials what types of benefits they deliver. We are using genetic and bioinformatics tools to find out which organisms are present during health, disease, post-treatment and over time. We are investigating how these bacteria function in their environment and in foods, and what benefits they accrue to the host, including blocking pathogens, modulating immunity, and breaking down or inhibiting toxic reactions.

The public and policymakers alike have been inundated with information about probiotics, and with a variety of media outlets and corporate advertisers spreading information, it is more important than ever that the scientific sector has a clear voice. CAST has released a new video based on its Issue Paper, Probiotics: Their Potential to Impact Human Health, as a contribution to scientific communication on this important topic. CAST Task Force Members Dr. Mary Ellen Sander (chairperson) and Dr. Todd Klaenhammer (reviewer) appear in the 8-minute video

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PmMM9-Mw87Q

Professor opts out of probiotic commercialisation route to concentrate on research Peter Ker

In a world in which scientists are often encouraged to commercialise their research findings, there's something quite noble about Gregor Reid.

He's a professor these days of microbiology and immunology at the University of Western Ontario, Canada, and director of the Canadian Research and Development Centre for Probiotics. (More info here)

When he first started researching the probiotic (good bacteria) over 25 years ago, it was considered a bit left field and unnecessary, since antibiotics were all that was considered necessary.

As time has gone on however with no new antibiotics and a growing bacterial resistance, the role of probiotics and their ability to crowd out harmful bacteria has become increasingly important.

As a Scotsman, who carried out his undergraduate studies at Massey University and gained a Canadian post-doctoral scholarship, Reid ended up working on women's urinary tract infections.

His research found that lactobacilli prevent infections by colonizing and outcompeting other more harmful varieties. Some of this research was patented, mostly around what the organism does and how it operates.

Monash University, where Reid did an MBA wanted to jointly commercialise the science, including potentially taking the resulting company to the NASDAQ.

"But I could see a potential conflict of interest, and had decided I didn't want to be in business," Reid says.

Two years ago the patent rights were sold, and is now sold as Flora Restore, a product to help vaginas repopulate with beneficial bacteria.

Reid is now able to concentrate more fully on the science of probiotics and how they work.

As antibiotic resistance grows, it also allows him to be at the forefront of probiotic's means of preventing infection.

Reid says future approaches to ridding patients of infections will not be as dependent on the 'carpet bombing' technique of antibiotics, but be much more strategic.

Genetic bioinformatics and gene sequencing will see much more personalised medicine happening in the future. The role of probiotics and prebiotics (something that stimulates the growth of beneficial organisms), will have a much more important role to play in tomorrow's medicine he says.

"There's no reason such products couldn't come from New Zealand," he says.

INTERVIEW

SW: Would you tell us a bit about your educational background and research experiences?

I earned my B.Sc. (Honours) degree in microbiology from the University of Glasgow in 1978, and my Ph.D. from Massey University, New Zealand, in 1982. I earned an Executive MBA degree from Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, in 1998.

I came to Canada in 1982 as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Calgary in Alberta, but shortly thereafter was based at Toronto General Hospital. I moved to London as Director of Research Services at the University of Western Ontario in 1990 and to Lawson Health Research Institute in 1996. In 2001, I was appointed the Chair of the United Nations/World Health Organization Expert Panel and Working Group on Probiotics.

I have received numerous awards over the years, most recently, the 2007 Elie Metchnikoff Prize for Nutrition and Health (with Dr. Andrew Bruce), an Honorary Doctorate in biology from the University of Orebro, Sweden, in 2008, an Endowed Research Chair in Human Microbiology and Probiotics in 2009, membership in the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences in 2009, and the Hellmuth Prize for most outstanding research at the University of Western Ontario in 2010.

Also, the Fem-Dophilus product Dr. Bruce and I created was voted one of the Top 10 Medical Breakthroughs in 2007 by the US's Prevention magazine, as well as the Best of Supplements by Better Nutrition magazine in 2008.

SW: What first drew your interest to probiotics?

I was really inspired by Dr. Andrew Bruce, who was head of Urology in Toronto when I joined in 1982. Back then, we didn't really call it "probiotics," but Dr. Bruce was very interested in the role of host microbiota and beneficial microbes in retaining and restoring health.

He felt that these microbes had a role to play, and so we started researching it, and it became exciting and almost addictive because we believed that there was truly something of value about these organisms.

Around 1986-87, we picked out one or two lactobacilli strains that we felt, if we administered them to the vaginas of women who had lost their natural lactobacilli, it might reduce their recurrences of infection. Our first clinical study was published in 1988 (Bruce AW, Reid G, "Intravaginal installation of lactobacilli for prevention of recurrent urinary-tract infections," Canadian Journal of Microbiology 34[3]: 339-43, March 1988).

The term "probiotics" had been loosely used and had different definitions over the years, but the concept hadn't really been taken seriously until the last 10 years or so.

SW: Several of your highly cited papers deal with the use of probiotic lactobacilli to restore and maintain urogenital flora. Would you talk a bit about this aspect of your work? How did you come to select Lactobacillus in particular?

In 1973, Dr. Bruce did a study in which he looked at the vaginal microbes from a group of women who suffered from recurrent bladder infections with E. coli (these bacteria come from the rectum, go into the vagina, then infect the bladder) and he found that the vagina was indeed heavily colonized by these pathogens.

On the contrary, the vaginas of women who had never suffered from UTI were colonized by lactobacilli, and he felt this was significant.

When I joined him in 1982 after he'd moved from McGill, we decided to look at lactobacilli. We had isolated a few strains and screened them for properties that we felt would be useful in colonizing the vagina and competing against pathogenic organisms.

danone affordable in africa?

SW: What is it about lactobacilli that make them protective?

Back in 1987, the method we used was whether lactobacilli could inhibit or kill pathogens in the lab, and adhere to the surface of the vagina. If they did that and competitively excluded pathogens from attaching, we selected them, but we still didn't know their mechanism in humans.

Of course, since then, science has advanced and it's safe to say we know an awful lot more now, albeit not the precise mechanisms. And so, in a sense, we were lucky in the organisms that we chose. If we had to start from scratch again, I don't know that we'd do the same in vitro experiments—they might be helpful in picking the organisms, but it doesn't mean they will work for sure in humans.

I think now we realize there are other factors; for example, creating an environment that the pathogen doesn't particularly like—reducing the pH, displacing the pathogen from binding to the surface, inhibiting or killing it, or in some cases downregulating the virulence properties of the pathogens without having to kill them.

The other mechanism is probably modulating the immune system, so that the host is fighting against the pathogen. We did one study where we looked at gene expression and it showed that some host defense genes were upregulated by Lactobacillus GR-1. So it's a combination of a number of things.

I don't believe that one Lactobacillus strain is a magic bullet. We found that we needed two strains because one is essentially very good against gram-negative organisms and a second strain competes against gram-positive pathogens.

I think you need to understand the place in which you're putting these organisms, what they do for host, and how they influence the micro-environment they're going into. Too many companies just seem to pick strains out of a hat, throw them all in, and hope something might work. That was never our approach—and I think it's the wrong approach.

SW: Four years ago, you talked about the importance of establishing guidelines for probiotics to aid their acceptance by the medical community in a paper for Current Pharmaceutical Design. What sort of progress would you say has been made towards this acceptance?

Regulatory agencies are now allowing companies to use the word "probiotics" on labels of food products, and they shouldn't be because that word has a definition that should be strictly adhered to. Essentially you have to prove that adding "probiotics" to products results in a properly documented benefit, usually by comparing it with placebo. Too few companies do this..

It's taken a long time, but I think we're turning a corner. Health Canada, for example, has come out with actually pretty strict guidelines that companies will have to adhere to, and I'm hoping it works—it's one thing to come out with policies and guidelines, it's another thing to have the people within the government to chase down the companies and say, "Sorry we're not letting you call this product a probiotic."

That's going to be very difficult, because I think in 2008 there were over 300 so-called probiotic products launched, and I'm betting you that less than 10 were really probiotic.

In Europe, EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) has not been as clear about what they want. I would much prefer if they'd say, "You provide us with A B C and D, and we'll let you have the following claims."

A lot of products have been rejected and it makes it sound like probiotics aren't reliable and haven't been proved to do anything if the European authorities aren't even allowing them to make claims, when in fact many of the ones that EFSA have rejected were quite rightly rejected—the strains or products don't do what is claimed.

Still, there are good products out there that I think should have approved claims, and hopefully they will very soon as consumers need to know what they are buying.

SW: How much do ordinary/healthy people need probiotics in their food, like yogurt, on a daily basis?

There's no evidence that you can take too many probiotics. I would say once or twice a day is fine, with, say, a food probiotic with breakfast and a capsule later in the day, depending on what you want the products to do for you.

So for lunch today I had Activia, because I quite like yogurt, and this product has been shown to improve gut function. If my wife was to take one, then she would take RepHresh Pro-B with the two strains that we developed because they're good for vaginal health. In fact, I could also take them because I know they have gut benefits, it's just they're not promoted for that purpose.

If I travel, which I do often, to countries where the food and water supplies are a bit dubious, then I'll take my strains and Saccharomyces boulardii, as they are in capsules that can be easily transported, with the aim of preventing diarrhea.

It's said that half of what we poop is bacteria and two to three pounds of our weight is bacteria in the gut, so how are we replenishing them? We presume that food does that and helps the beneficial bacteria multiply in your gut, but that's not necessarily the case. While many foods need to be eaten fresh, even 50 years ago, a lot are now sterilized or processed, so that's one reason I take probiotics daily to compensate.

More recently, you've done some work with the use of probiotics in HIV/AIDS patients as well as natural food sources of probiotics in Africa. What sort of impact do you think probiotics might have on the health of HIV/AIDS patients and people in general in these regions of the world?

It started with Stephen Lewis, who was the United Nations' special envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa—he gave a talk at the university. I wasn't there, but a colleague of mine, Bob Gough, was. In addition to being impressed with Stephen's wonderful oratory skills, he inspired Bob to say, "Look, I'm in charge of housing at the university and we have about 6-7,000 first-year students who could become engaged and do something for HIV in Africa."

For whatever reason, he called me and I went to a meeting. It was kind of strange, people from Housing discussing what they could do for Africa.

My feeling was that if you're going to do something like this, it has to be sustainable. You can't be airlifting supplies every week; that doesn't help the country. It has to be something that when you walk away, they can continue on their own.

It also should be something that can affect everybody, something that can be purchased by extremely poor people. Also, with the rates of malnutrition and HIV, many people get diarrhea or some kind of gut problems. So putting all that together, I said, "Well, why don't we make a probiotic yogurt?"

So that was the goal. I donated the strain, Dr. Shari Hekmat devised a yogurt with it, and two student interns went out to Tanzania, Africa, and set up a kitchen by teaching local mothers how to make probiotic yogurt. Western Heads East was born.

Now we have this whole network running on the ground, and I think that's why it's successful. Often, well-intentioned initiatives peter out, because people don't engage grass-root local scientists and politicians and NGO's.

The women are incredibly dedicated. We're talking about an environment where 80% of people share pit toilets and unemployment is like 60%—in many cases survival comes through selling a couple of pieces of corn every day. There are electricity shortages...it's just extremely challenging.

And yet these mothers—some of whom faced violence from male partners upset because they believed their women should stay home and take care of them and their children—out of all these challenges, stuck with it, set up an NGO, and have now helped the concept go to Kenya and soon Rwanda, and hopefully other regions.

They're determined to be a grassroots organization for the poor, and for us, it's been incredible to send out interns (the real heroes and heroines) for several months of internship work. Most of them get malaria or some kind of sickness, and yet they come back so motivated and changed as people.

In terms of the science, it's very difficult to do it because there is only have one ethics review board for the whole country and so it took nine months to get approval for one study. Nobody seems to want to fund this kind of work, maybe because they see it as too low tech. I've had situations where people say, "Pfft! Yogurt! That's not going to help people."

We have got some data coming in slowly but surely and the results indicate that the probiotic yogurt can reduce diarrhea, improve energy levels, reduce side effects from antiretroviral therapy (these drugs themselves can kill you), and improve nutrition, etc.

We never said we'd cure AIDS; what we're trying to do is help the quality of life, help people with the virus, and I think we're doing that.

SW: Where do you see probiotics going in the next decade?

If you have a slide of the human body, you could point to any part of it, and you'll find that microbes play a role in health. And so, the sky's the limit, really. Probiotics at present represents somewhat of a crude way of manipulating that flora, but it will become more targeted.

We're dead without our organisms; it's as simple as that. There's not a human being alive who doesn't have microbes. We came from these organisms and so they're integral to everything that we do—they affect every part of us.

For example, in the bloodstream, lactobacilli might help to lower cholesterol. In the brain, recent papers have shown reduced anxiety or pain if you take probiotics. You can go through papers on reduced duration of respiratory infections, bladder cancer—it's really hard to find a part of the body probiotics don't affect. There's already some work showing that probiotics could impact obesity.

Probiotics is one way of restoring beneficial organisms. In the future, we will take specific strains at specific times. For example, I have a neighbor with really, really bad allergies, causing lesions all over his legs and hospitalization a couple of time every summer due to these allergies. We put him in a study where we made a probiotic yogurt and he was in the active arm rather than the placebo.

He had a great summer. He was raving about it: "God what was in this stuff?" He had hardly any issues with allergies at all. So I said to him, "Well, the study is over, but if you take DanActive, it's at least worth trying."

He's been on that for a year and a half now, and I think last summer he may have taken an antiallergy medication once. He totally swears by the yogurt. In his case, I think it's had a massive, massive effect. You can feel better with placebo, but that won't stop the lesions coming out, so I feel it is the product that has helped him.

There are a lot of examples like that, but as a scientist I need to try and find out what works, why it works in some people and not in others.

I just wrote a paper which will come out in Gut Microbes, probably later on in 2010, on responders and nonresponders. It comes from a meeting I hosted as president of ISAPP (International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics) in November 2009, in which we explored why some people respond well and others not at all to probiotics and medications.

Part of the reason is the selection criteria for entering the study and part of it is the genetics of how someone responds. So by carefully planning the study and using predictors of who will respond, I think we'll find that we can improve the number of people who respond in future studies.

In the next 20 years you will see many more applications. They might be more complicated, they'll probably be more targeted. More personalized medicine will find its place. So a patient will be able to say "I'm 38, I want to get pregnant," or "I'm menopausal," or whatever..."This I what I want the probiotic for," and so you'll have a range of different strains to choose from based upon your flora, age, health status, etc.

Until very recently, not one of us did anything for our flora. We didn't take one piece of food and say, "I'm taking this because I want my beneficial flora to be enhanced." Tomorrow, you just might do that!

END

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home